BIOGRAPHY:

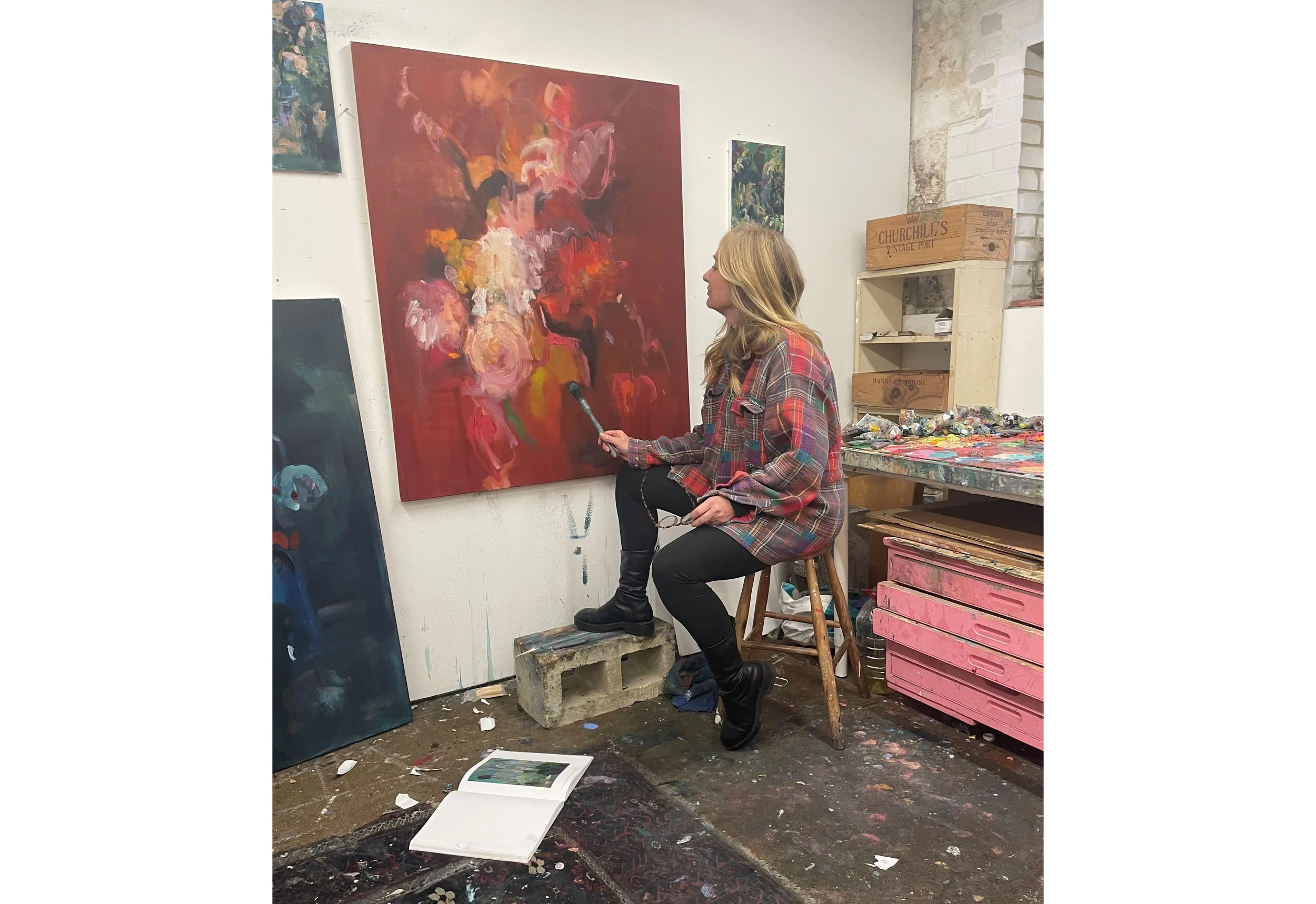

Jayne Sandys-Renton is a painter focusing on nature and women. Her dense, interior landscapes invite the viewer to experience colour and gesture in these expressive, bold works that dip into fairy tale, myth, and transformation. Her recent paintings use 18th century Dutch flower paintings as her intro.

Born in London, Jayne began painting from a young age before moving to Sussex. Receiving a BA (Hons) Fine Art from the University of Chichester (2003), and an MA with Distinction awarded by the University of Sussex at West Dean College (2008). In 2018 Jayne wanted to re-invigorate her practice and enrolled on the Turps Correspondence Course 2018/19 and 2019/20, mentored by the artists Hanna Murgatroyd and Sarah Pickstone; this had a profound effect on her work.

Jayne has works in collections across Britain, in Rhode Island (Boston, USA) and Germany, and has exhibited regularly in London and the South of England. In March 2009 she made a joint presentation paper with Stephanie Norgate, published poet, at ‘The Lonely Page’ conference, The Seamus Heaney Centre, Queen’s University Belfast (see p.66 of https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_200861_smxx.pdf). In 2009 she was in the exhibition ‘5×5’ in the Sussex Barn Gallery, West Dean. The following year (2010) Jayne collaborated again with the poet Stephanie Norgate on ‘Fallen House and Other Voices’ at the Otter Gallery, and had a solo show at the Joy Gallery, Chichester. In 2014 she had solo exhibitions at The Valdoe Barn in Goodwood, Gallery Muse in Petersfield, and West Dean College. In 2016, following two summer residencies at the Cyprus School of Art, Lemba, Paphos, she collaborated with her husband on an exhibition Millennial Lines at The Cornaro Institute in Larnaka, Cyprus. In 2018 she had a solo exhibition at 'Midmar' in Bath. In 2021 she exhibited in the Turps Banana ‘In Absentia’, group exhibition with Cohort.Art. In 2021 she exhibited in the all-woman group exhibition 'Forces of Nature’ organised by Gallery 94 at Glyndebourne, and in 2022 was selected for the Oxmarket Contemporary ‘Open 22’ and was guest artist at Hotwalls Studios, Portsmouth, in March 2023. She continues to show and sell her work.

Jayne currently has work in the Wightman Gallery, Saffron Walden, Cambs, until 23 December 2025 https://wightmangallery.com/, female artists redefining ‘the muse’.

ARTIST STATEMENT - 2023

My paintings begin with an intense feeling that is created by nature and by women who have meaning for me. Within my paintings I allude to a space, but ultimately it is a space of the imagination, an entanglement of gestural marks and intense colour, layers of paint that dip into memory, myth, and fairy tale; a metaphor for psychology, emotion or relationships. These ‘landscape interiors’ are often without a horizon, dense with vegetation, moving towards abstraction. While the work may be a direct response to nature itself, it invites a feeling of otherworldliness, creating ideas of transformation, hinting at a presence; maybe a figure will emerge as if borne of the landscape. Women are always implicitly present in my work, even if not literally apparent.

Bonnard and Rubens (amongst others) influence colour and space, with some of my paintings reworking old masters to give an enhanced sense of chaotic nature seeping from the canvas. Colour, form and brush marks veer toward the abstract in some paintings. Joan Mitchell is an important reference, as is Cecily Brown. These two women artists form a key and consistent inspiration, together with more classical influences.

I start work in several ways. When I go outside and paint, I am observing, entranced, digging deep into the foliage, landscape or place. In the studio these works are used as a springboard to unleash other experiences. For example, within the dense layers of flowers and leaves I can place a Rubens figure or imagine the wood nymph Echo discarded by Narcissus. So, in this sense I am often transforming the original observed piece into an imagined place. What the painting might mean comes to me as the painting forms. I research to create an energy; a dynamic response to a source that is not predetermined but evolves.

As a child, my mother read me fairytales, a tradition I continued with my daughters. During lockdown my daughters returned home and entered my paintings. As I observed them in the garden, I imagined Lupa, the She-Wolf, Alice in Wonderland, full of adolescent letting go and on the threshold of womanhood. Strength and vulnerability coalesced in the paintings, uniting the mythic with the personal and familial.

When I am in a garden, forest, or landscape, I see layers that pile on top of each other, and I can look through them as if each layer is separately visible. The branch overlaying the flower, overlaying the leaves, overlaying the earth. In turn when I paint them, they become dense interior spaces, while remaining exteriors, celebrating non-human interdependence and yet overlaid by human emotion.

The more recent sequence of flower paintings arose from a visit to the Dulwich Picture Gallery. Winter had stripped nature of its density. In the museum, as I viewed the detailed still-life flower paintings by the Dutch old master Jan Van Huysum through half-closed eyes, their flowing composition and delicious colour became almost abstract. To paint from them posed an interesting contrast to the usual way I looked at nature. The flowers painted by Jan Van Huysum bloom at different times of year so cannot be painted as a group. The unseasonal artificiality of the paintings took me beyond their apparent realism to contemporary notions of manipulating nature. The constructed composition of petals on dark backgrounds held a splendid grandeur that I could transform into metaphors, exploring growth, together with mortality and fragility.

Recent Work: Jayne Sandys-Renton | by Dr. Mike Walker

The recent paintings made by Jayne Sandys-Renton over the last twelve to eighteen months are the culmination of gradual shifts in her practice that have been slowly building, so what seems like a sudden emergence has, in fact, been steadily prepared for. You can see it most clearly in a set of paintings she made based on stills from film versions of Alice in Wonderland in which the legibility of forms has been eroded, so that Alice emerges, if at all, from a mesh of painterly marks that have begun to block illusionistic space and stay more resolutely on the picture plane. The Alice paintings stay with the dark, brooding, monochrome palette of much of Jayne’s earlier work, but this is resolutely dispelled in another set of paintings called All I Desire, in which the female figure is swathed in rich bright colour. These two changes in her practice, to a much brighter palette and away from easily readable representational forms, come together in the new paintings.

There is still clearly a landscape involved and, frequently, there is a female figure, but these no longer dictate the mark-making or the compositional build up of form and colour. The mesh of painterly marks, drawing on a wide range of brushes and knives, used every which way to create a virtuosic variety of smears, dabs, lines, splashes, scrapings and overlays, is dominated by long straggling verticals which hang down like vines or drooping branches, so that we peer through to a space beyond. This is about the only concession to illusionistic space and even here, the insistent rhythm of those verticals, and their thick application of dragged paint, threatens to close the space down. They are interrupted by a secondary set of marks, spidery, which weave in and out and create the sense of a dense, abundant undergrowth, but once again the evocation of landscape elements is tentative, constantly threatening to collapse into the painted surface of the canvas. Threshold (2019) can quite easily be read as a flowery glade, or else as some other kind of threshold, beyond which form is no longer legible and has to be reconstructed in other ways. The long tendrils with pink tips in Sugar and Spice (2019) are clearly some kind of flower, then the dabs of colour float free of that association and begin to transmute, ultimately hovering between a range of possible readings and the literal presence of the paint.

Such ambiguities of representational form would normally be considered in terms of abstraction, but it might be useful to think of what is happening in these paintings phenomenologically, in relation to notions of determinacy and indeterminacy. In The Phenomenology of Perception (1945) Maurice Merleau-Ponty posits the notion of maximum grip, which amounts to almost an instinctive drive to clarify what it is we are perceiving until we have a firm grasp upon the qualities and features, the identity, of what is before us. When confronted with what he calls the phenomenal field - the world before we have had chance to process it and turn perception into information - we often have to make sense of what is indeterminate. An example he gives is of some tall dark tree-like forms in the distance which eventually resolve themselves - we resolve them - into the masts of ships. This passage from the indeterminate to the determinate is what characterises the operation of perception and, it seems to me, these paintings engage with that transitional process. If we look at Moon Child of 2019, for instance, we move from the forest-like forms of the upper half of the canvas to a set of shapes which are impossible to pin down to any definitive reading. What does the pale circle of flesh-coloured paint represent? And what are the group of form-marks beneath? In order to come to any reading of these forms we would have to be able to locate them in depth - exactly the kind of perceptual judgement which depends upon our ‘grip’ - but this proves impossible. The marks shift between the nearer space of the red splotches of flowers and a middle distance, leaving us unable to judge what their actual size might be, their precise location and, ultimately, their identity.

It is important to differentiate this deliberate strategy of perceptual ambiguity from the lapses in legibility to which most representational painting is prone. Sandys-Renton could easily have clarified the forms in Moon Child but we know that she resisted such a move because the entire sequence of recent paintings dramatises exactly this loss of legibility and sets out to explore its implications. That loose conglomeration of marks beneath the fleshy loop in Moon Child conjures, for this viewer at least, the slippery dissolution of the human body which became central to Willem deKooning’s work from the mid-sixties onwards. In other paintings the human figure is held onto more tenaciously, evoking the way in which Cecily Brown always allows the viewer to identify, to pull out, bodily forms from a mesh of seemingly abstract marks. Such painters exploit the contested terrain which lies between what we call representational and abstract painting. They call into question the way in which we view paintings, whether that be the taken-for-granted understanding of the representational, what Richard Wollheim terms seeing-in, or the deliberate blocking of such seeing-in which is involved with our notion of abstraction and they do so in order to create a more fluid situation, one that allows space for indeterminacy.

This perceptual fluidity allows for surprises, such as the figure in Lupa (2019) which, in front of the actual painting, at first evades us, only to erupt into our consciousness at a later point in the viewing process. Such surprises are more than optical tricks. They are a way of holding back the processing of perception into information, that all-too efficient human ability which Merleau-Ponty connects to the more general reduction of the world he calls objective thinking. They remind us that paintings are not pieces of information, or theoretical lessons to be learned, but a particular kind of experience which allows for the active engagement of the viewer. In these paintings we enter a space which, holding onto the indeterminate, we have to define for ourselves.

© Dr. Mike Walker